chamber is known from testimonies reported by Father Krzysztof Dunin-Wasowicz, there has been no scientific examination of the “murder weapon” since 1945, which means that we do not know how the chamber functioned as a delousing installation and are unable to provide material proof of its criminal, use. The number of victims is estimated a one or two thousand.

The visit did not greatly impress us. We were young and in love, and our car, a Renault 4L, was in a hurry to get to Gizycko, formerly Lötzen, on the shores of lake Niegocin in Mazuria. Our canoe expeditions, which led us to deserted islands surrounded by protective reeds, have left indelible memories. Love is an agreeable pastime tor two students of opposite sex but it is not very enriching for the intellect. In order to meet this latter need we devoted one day to visiting, near the village of Gierloz the Rastenburg Führer Headquarters known as “Wolfsschanze” or “Wolf’s Lair”, Hitler’s advance command post for the operations in Russia. These colossal bunkers are now the dislocated ruins [Photo7] of totalitarian pride, but though they are choked by trees and other vegetation, they still exhude a disquieting power, and are still dangerous because the area is full of mines, only a small proportion of which have been neutralized. One of the concrete roads leads to a clearing where Hitler enjoyed presentations of different prototype tanks, such as the “mouse”, a tank of 189 tons, proudly carrying at 20 kmh one 150 mm gun and one 75 mm. The Reichskanzler combined the mentality of a mole with a taste tor heavy objects. The bunker walls, of staggering thickness, had been fitted with explosives, so that in January 1945 the Germans set off an enormous explosion that destroyed the bunker-city and caused many of the lower levels to be flooded by the waters of the surrounding lakes.

After our self-indulgent idleness on the shores of the lakes, spoilt only by atrocious food, we headed south towards the second camp. Treblinka, the one that had inspired our trip to Poland. It was difficult to find, the rare signposts being silent as to its location. At Stutthof I had hought a guide to the “Places of struggle and martyrdom”. Reckoning that we must be very close, I saw an isolated house and, armed with my guide book and a photograph, went to ask where the former extermination camp was located. I was told they did not know. Disappointed, I continued along the road and a few hundred meters further on, beyond a screen of trees, saw the mushroom-like Treblinka II monument-mausoleum [Photo 8], surrounded by a symbolic cemetery of, apparently, 17000 standing stones. The three Polish artists who collaborated on the monument must have been inspired by unconscious cynical humour. Their bedtime reading apparently did not include the book of the “Stürmer”, (Julius Stretcher’s anti-semitic journal), addressed “to young and old” entitled “Der Giftpilz”, in which the Jews are assimilated to poisonous toadstools. At the entrance to the camp the former railway was represented by cement sleepers that suddenly stopped. Not a soul to be seen. Completely deserted. If I had become aware of Polish nationalism at Malbrock. I began to see at Treblinka an attitude towards the Jews that I had not previously suspected.

There was NOTHING left of the former camp. There were absolutely no facilities whatever tell visitors: no entrance, no guard, no guide. not even a kiosk selling postcards, books or pamphlets in memory of the 800,000 (official figure) Jewish victims who had gone up in smoke. This abundance of “Nie ma” did not keep us long and we reached Warsaw at dusk. In the middle of August, the capital was dead after 9 o'clock. The night life that we were seeking outside the hotel was actually IN the hotel and we had not even noticed it. How sad it must have been to be young in Warsaw in August 1964, in a city only half rebuilt and dominated by the towering 234 meters of the Palace of Culture and Science donated by Stalin, “the little father of the people”. Such was our impression as French students discovering heroic “Warzawa”. We could not imagine what Warsaw must have been like after its Liberation on 17th January 1945. Trying to imagine TWO THOUSAND Oradours all merged into one is beyond the powers of a Frenchman. Visually materializing this tragic annihilation would have meant going through all the streets of Oradour 2000 times the in winter of 1944. Only an album published in 1985 by the State Scientific Publishing House gives a glimpse of “WARSAWA 1945”. These photographs of a city devastated, sacked, pillaged, dynamited and burned, taken under conditions so difficult that there was even a lack of water for developing the films, represent the despairing observation of their author, Leonard Sempolinski. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

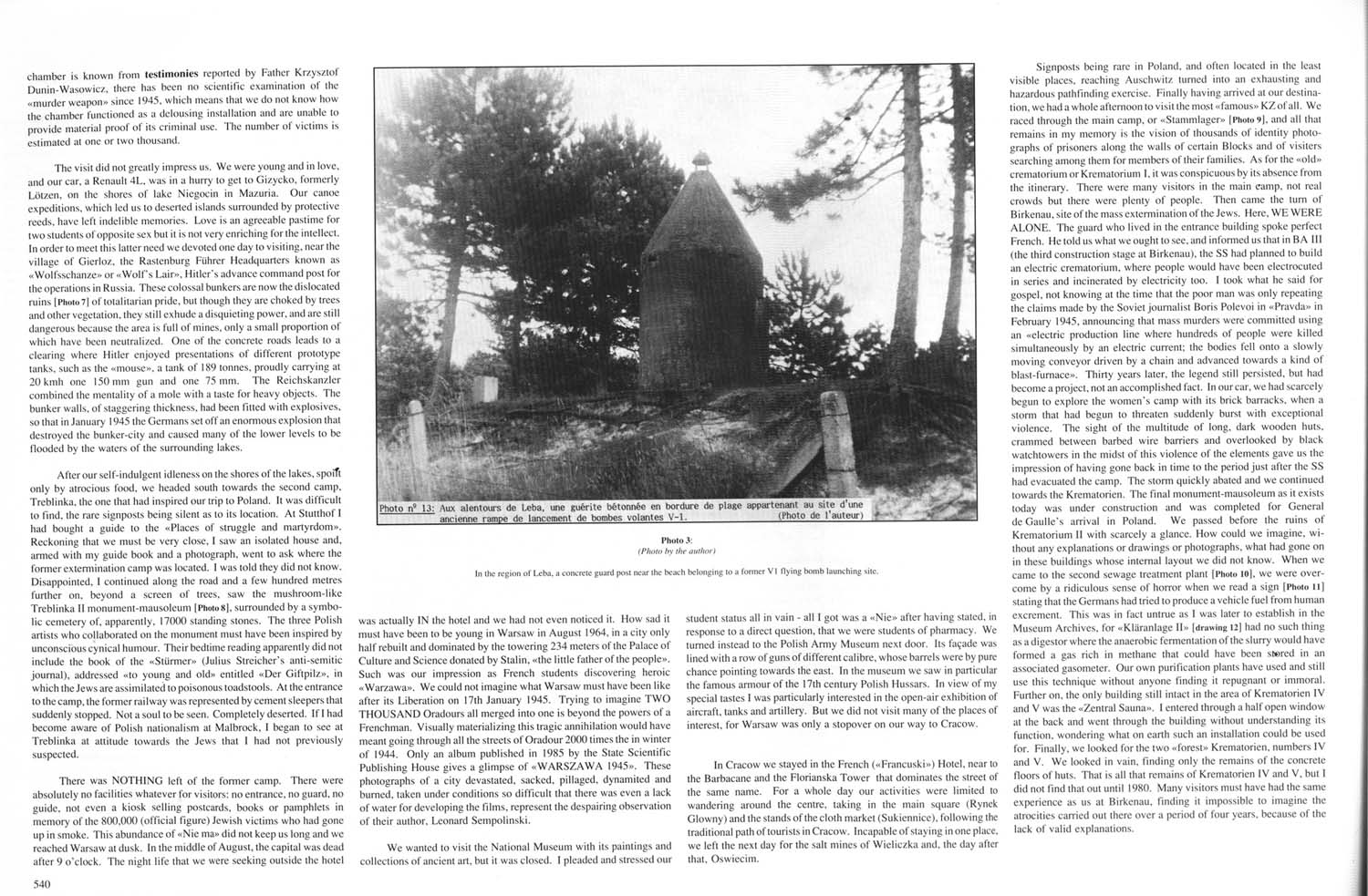

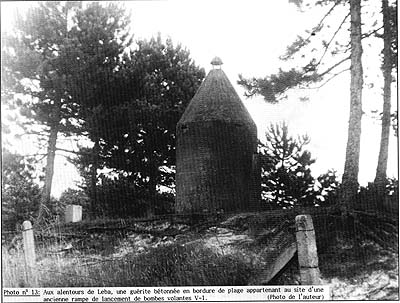

Photo 3:

(Photo by the author) |

|

| |

In the region of Leba, a concrete guard post near the beach belonging to a former V 1 flying bomb launching site. |

|

|

We wanted to visit the National Museum with its paintings and collections of ancient art, but it was closed. I pleaded and stressed our student status all in vain — all I got was a “Nie” after having stated, in response to a direct question, that we were students of pharmacy. We turned instead to the Polish Army Museum next door. Its façade was lined with a row of guns of different calibre, whose barrels were by pure chance pointing towards the east. In the museum we saw in particular the famous armour of the 17th century Polish Hussars. In view of my special tastes I was particularly interested in the open-air exhibition of aircraft, tanks and artillery. But we did not visit many of the places of interest, for Warsaw was only a stopover an our way to Cracow.

In Cracow we stayed in the French ("Francuski") Hotel, near to the Barbacane and the Florianska Tower that dominates the street of the same name. Far a whole day our activities were limited to wandering around the center, taking in the main square (Rynek Glowny) and the stands of the cloth market (Sukiennice ), following the traditional path of tourists in Cracow. Incapable of staying in one place, we left the next day for the salt mines of Wieliczka and, the day after that, Oswiecim.

Signposts being rare in Poland, and often located in the least visible places, reaching Auschwitz turned into an exhausting and hazardous pathfinding exercise. Finally having arrived at our destination, we had a whole afternoon to visit the most “famous” KZ of all. We raced through the main camp, or “Stammlager” [Photo 9], and all that remains in my memory is the vision of thousands of identity photographs of prisoners along the walls of certain Blocks and of visitors searching among them for members of their families. As for the “old” crematorium or Krematorium I, it was conspicuous by its absence from the itinerary. There were many visitors in the main camp, not real crowds but there were plenty of people. Then came the turn of Birkenau, site of the mass extermination of the Jews. Here, WE WERE ALONE. The guard who lived in the entrance huilding spoke perfect French. He told us what we ought to see, and informed us that in BA III (the third construction stage at Birkenau), the SS had planned to build an electric crematoriunn. where people would have been electrocuted in series and incinerated by electricity too. I took what he said for gospel, not knowing at the time that the poor man was only repeating the claims made by the Soviet journalist Boris Polevoi in “Pravda” in February 1945, announcing that mass murders were committed using an “electric production line where hundreds of people were killed simultaneously by an electric current: the bodies fell onto a slowly moving conveyor driven by a chain and advanced towards a kind of blast-furnace”. Thirty years later, the legend still persisted, but had become a project, not an accomplished fact. In our car, we had scarcely begun to explore the women’s camp with its brick barracks, when a storm that had begun to threaten suddenly burst with exceptional violence. The sight of the multitude of long, dark wooden huts, cramped between barbed wire barriers and overlooked by black watchtowers in the midst of this violence of the elements gave us the impression of having gone back in time to the period just after the SS had evacuated the camp. The storm quickly abated and we continued towards the Krematorien. The final monument-mausoleum as it exists today was under construction and was completed for General de Gaulle’s arrival in Poland. We passed before the ruins of Krematorium II with scarcely a glance. How could we imagine, without any explanations or drawings or photographs, what had gone on in these buildings whose internal layout we did not know. When we came to the second sewage treament plant [Photo 10], we were overcome by a ridiculous sense of horror when we read a sign [Photo 11] stating that the Germans had tried to produce a vehicle fuel from human excrement. This was in fact untrue as I was later to establish in the Museum Archives, for “Kläranlage II” [drawing 12] had no such thing as a digestor where the anaerobic fermentation of the slurry would have formed a gas rich in methane that could have been stored in an associated gasometer. Our own purification plants have used and still use this technique without anyone finding it repugnant or immoral. Further on, the only building still intact in the area of Krematorien IV and V was the “Zentral Sauna”. I entered through a half open window at the back and went through the building without understanding its function, wondering what on earth such an installation could be used for. Finally, we looked for the two “forest” Krematorien, numbers IV and V. We looked in vain, finding only the remains of the concrete floors of huts. That is all that remains of Krematorien IV and V, but I did not find that out until 1980. Many visitors must have had the same experience as us at Birkenau, finding it impossible to imagine the atrocities carried out there over a period of four years, because of the lack of valid explanations. |

|