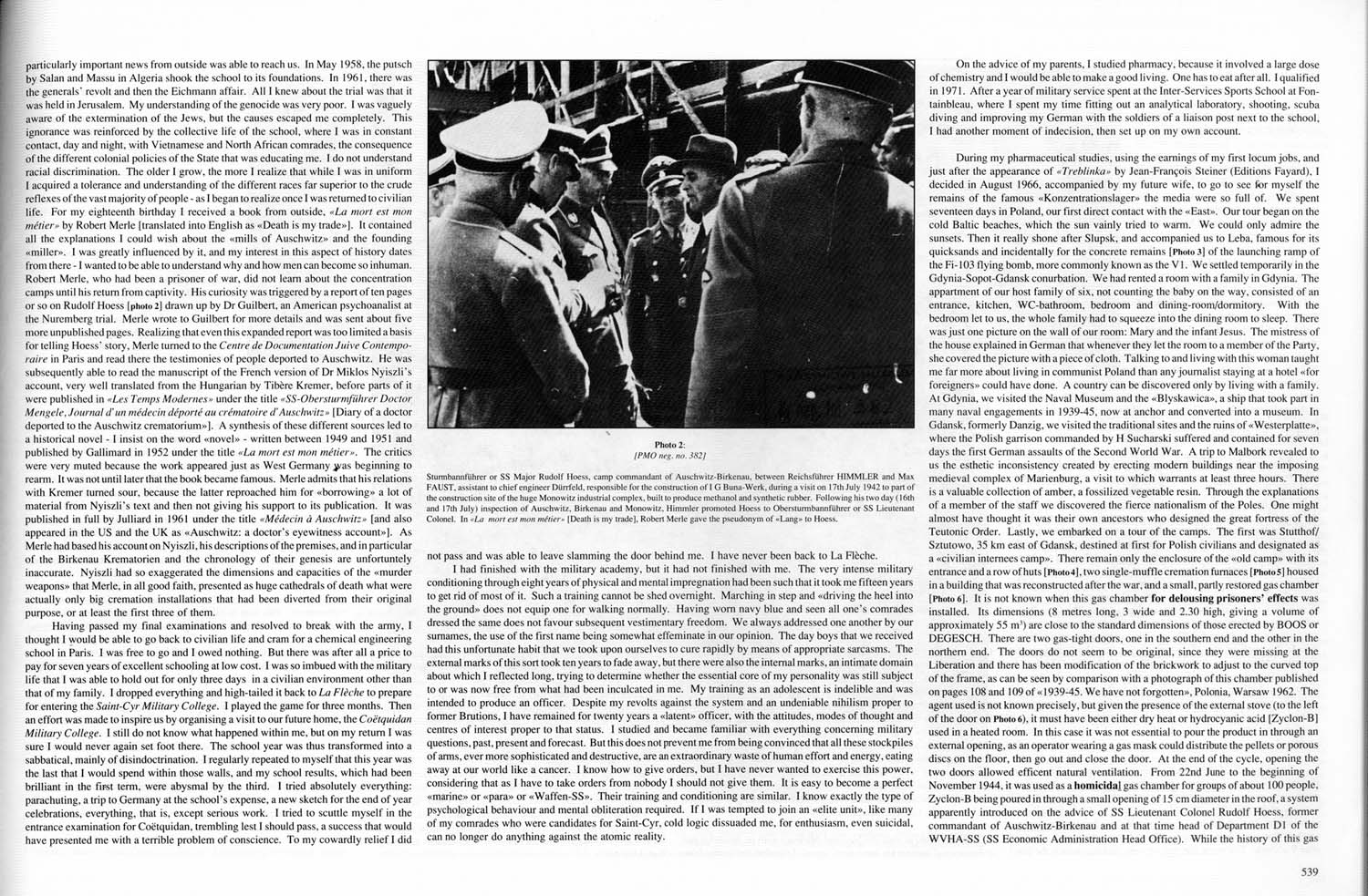

particularly important news from outside was able to reach us. In May 1958, the putsch by Salan and Massu in Algeria shook the school to its foundations. In 1961, there was the generals’ revolt and then the Eichmann affair. All I knew about the trial was that it was held in Jerusalem. My understanding of the genocide was very poor. I was vaguely aware of the extermination of the Jews, but the causes escaped me completely. This ignorance was reinforced by the collective life of the school, where I was in constant contact, day and night, with Vietnamese and North African comrades, the consequence of the different colonial policies of the State that was educating me. I do not understand racial discrimination. The older I grow, the more I realize that while I was in uniform I acquired a tolerance and understanding of the different races far superior to the crude reflexes of the vast majority of people — as I began to realize once I was returned to civilian life. For my eighteenth birthday I received a book from outside. “La mort est mon métier” by Robert Merle [translated into English as “Death is my trade”]. It contained all the explanations I could wish about the “mills of Auschwitz”, and the founding “miller”. I was greatly influenced by it, and my interest in this aspect of history dates from there — I wanted to be able to understand why and how men can become so inhuman. Robert Merle, who had been a prisoner of war, did not learn about the concentration camps until his return from captivity. His curiosity was triggered by a report of ten pages or so on Rudolf Hoess [Photo 2] drawn up by Dr Guilbert, an American psychoanalist at the Nuremberg trial. Merle wrote to Guilbert for more details and was sent about five more unpublished pages. Realizing that even this expanded report was too limited a basis for telling Hoess' story, Merle turned to the Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaire in Paris and read there the testimonies of people deported to Auschwitz. He was subsequently able to read the manuscript of the French version of Dr Miklos Nyiszli’s account, very well translated from the Hungarian by Tibere Kremer, before parts of it were published in “Les Temps Moderne” under the title “S.S-Obersturmführer Doctor Mengele, Journal d'un médecin déporté au crématoire d'Auchwitz” [“Diary of a doctor deported to the Auschwitz crematorium”]. A synthesis of these different sources led to a historical novel — I insist on the word “novel” — written between 1949 and 1951 and published by Gallimard in 1952 under the title “La mort est mon métier”. The critics were very muted because the work appeared just as West Germany was beginning to rearm. It was not until later that the book became famous. Merle admits that his relations with Kremer turned sour, because the latter reproached him for “borrowing” a lot of material from Nyiszli’s text and then not giving his support to its publication. It was published in full by Julliard in 1961 under the title “Médecin à Auschwitz” [and also appeared in the U.S. and the UK as “Auschwitz: a doctor’s eyewitness account”]. As Merle had based his account on Nyiszli, his descriptions of the premises, and in particular of the Birkenau Krematorien and the chronology of their genesis are unfortuntely inaccurate. Nyiszli had so exaggerated the dimensions and capacities of the “murder weapons” that Merle, in all good faith, presented as huge cathedrals of death what were actually only big cremation installations that had been diverted from their original purpose, or at least the first three of them.

Having passed my final examinations and resolved to break with the army. I thought I would he able to go back to civilian life and cram for a chemical engineering school in Paris. I was free to go and I owed nothing. But there was after all a price to pay for seven years of excellent schooling at low cost. I was so imbued with the military life that I was able to hold out for only three days in a civilian environment other than that of my family. I dropped everything and high-tailed it back to La Flèche to prepare for entering the Saint-Cyr Military College. I played the game for three months. Then an effort was made to inspire us by organising a visit to our future home, the Coëtquidan Military College. I still do not know what happened within me, but on my return I was sure I would never again set foot there. The school year was thus transformed into a sabbatical, mainly of disindoctrination. I regularly repeated to myself that this year was the last that I would spend within those walls, and my school results, which had been brilliant in the first term, were abysmal by the third. I tried absolutely everything: parachuting, a trip to Germany at the school’s expense, a new sketch for the end of year celebrations, everything, that is, except serious work. I tried to scuttle myself in the entrance examination for Coëtquidan, trembling lest I should pass, a success that would have presented me with a terrible problem of conscience. To my cowardly relief I did not pass and was able to leave slamming the door behind me. I have never been back to La Flèche.

[PMO neg. no. 382]

Sturmbannführer or SS Major Rudolf Hoess, camp commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau, between Reichsführer HIMMLER and Max FAUST, assistant to chief engineer Dürrfeld, responsible for the construction of I G Buna-Werk, during a visit on 17th July 1942 to part of the construction site of the huge Monowitz industrial complex, built to produce methanol and synthetic rubber. Following his two day (16th and 17th July) inspection of Auschwitz, Birkenau und Monowitz, Himmler promoted Hoess to Obersturmbannführer or SS Lieutenant Colonel. In “La mort est mon métier” [Death is my trade], Robert Merle gave the pseudonym of “Lang” to Hoess.

I had finished with the military academy, but it had not finished with me. The very intense military conditioning through eight years of physical and mental impregnation had been such that it look me fifteen years to get rid of most of it. Such a training cannot he shed overnight. Marching in step and “driving the heel into the ground” does not equip one for walking normally. Having worn navy blue and seen all one’s comrades dressed the same does not favour subsequent vestimentary freedom. We always addressed one another by our surnames, the use of the first name being somewhat effeminate in our opinion. The day boys that we received had this unfortunate habit that we took upon ourselves to cure rapidly by means of appropriate sarcasms. T'he external marks of this sort took ten years to fade away, but there were also the internal marks, an intimate domain about which I reflected long, trying to determine whether the essential core of my personality was still subject to or was now free from what had been inculcated in me. My training as an adolescent is indelible and was intended to produce an officer. Despite my revolts against the system and an undeniable nihilism proper to former Brutions, I have remained for twenty years a “latent” officer, with the attitudes, modes of thought and centers of interest proper to that status. I studied and became familiar with everything concerning military questions, past, present and forecast. But this does not prevent me from being convinced that all these stockpiles of arms ever more sophisticated and destructive, are an extraordinary waste of human effort and energy, eating away at our world like a cancer. I know how to give orders. but I have never wanted to exercise this power, considering that as I have to take orders from nobody I should not give them. It is easy to become a perfect “marine” or “para” or “Waffen-SS”. Their training and conditioning are similar. I know exactly the type of psychological behaviour and mental obliteration required. If I was tempted to join an “elite unit”, like many of my comrades who were candidates for Saint-Cyr, cold logic dissuaded me, for enthusiasm, even suicidal, can no longer do anything against the atomic reality.

On the advice of my parents, I studied pharmacy, because it involved a large dose of chemistry and I would be able to make a good living. One has to eat after all. I qualified in 1971. After a year of military service spent at the Inter-Services Sports School at Fontainbleau, where I spent my time fitting out an analytical laboratory, shooting, scuba diving, and improving my German with the soldiers of a liaison post next to the school, I had another moment of indecision, then set up on my own account.

During my pharmaceutical studies, using the earnings of my first locum jobs, and just after the appearance of “Treblinka” by Jean-François Steiner (Editions Fuyard), I decided in August 1966, accompanied by my future wife to go to see for myself the remains of the famous “Konzentrationslager” the media were so full of. We spent seventeen days in Poland, our first direct contact with the “East”. Our tour begun on the cold Baltic beaches, which the sun vainly tried to warm. We could only admire the sunsets. Then it really shone after Slupsk. and accompanied us to Leba, famous for its quicksands and incidentally for the concrete remains [Photo 3] of the launching ramp of the Fi-103 flying bomb, more commonly known as the V 1. We settled temporarily in the Gdynia-Sopol-Gdansk conurbation. We had rented a room with a family in Gdynia. The apartment of our host family of six, not counting the baby on the way, consisted of an entrance kitchen, WC-bathroom, bedroom and dining-room/dormitory. With the bedroom let to us. the whole family had to squeeze into the dining room to sleep. There was just one picture on the wall of our room: Mary and the infant Jesus. The mistress of the house explained in German that whenever they let the room to a member of the Party, she covered the picture with a piece ofcloth. Talking to and living with this woman taught me far more about living in communist Poland than any journalist staying at a hotel “for foreigners” could have done. A country can be discovered only by living with a family. At Gdynia, we visited the Naval Museum and the “Blyskawica”, a ship that took part in many naval engagements in 1939-45. now at anchor and converted into a museum. In Gdansk, formerly Danzig, we visited the traditional sites and the ruins of “Westerplatte”, where the Polish garrison commanded by H Sucharski suffered and contained for seven days the first German assaults of the Second World War. A trip to Malbork revealed to us the esthetic inconsistency created by erecting modem buildings near the imposing medieval complex of Marienburg, a visit to which warrants at least three hours. There is a valuable collection of amber, a fossilized vegetable resin. Through the explanations of a member of the staff we discovered the fierce nationalism of the Poles. One might almost have thought it was their own ancestors who designed the great fortress of the Teutonic Order. Lastly, we embarked on a tour of the camps. The first was Stutthof / Sztutowo, 35 km east of Gdansk,. destined at first for Polish civilians and designated as a “civilian internees camp”. There remain only the enclosure of the “old camp” with its entrance and a row of huts [Photo 4], two single-muffle cremation furnaces [Photo 5] housed in a building that was reconstructed after the war, and a small. partly restored gas chamber [Photo 6]. It is not known when this gas chamber for delousing prisoners' effects was installed. Its dimensions (8 meters long, 3 wide and 2.30 high, giving a volume of approximately 55 m³) are close to the standard dimensions of those erected by BOOS or DEGESCH. There are two gas-tight doors, one in the southern end and the other in the northern end. The doors do not seem to be original, since they were missing at the Liberation and there has been modification of the brickwork to adjust to the curved top of the frame, as can be seen by comparison with a photograph of this chamber published on pages 108 and 109 of “1939-45. We have not forgotten” Polonia, Warsaw 1962. The agent used is not known precisely, but given the presence of the external stove (to the left of the door on Photo 6), it must have been either dry heat or hydrocyanic acid [Zyklon-B] used in a heated room. In this case it was not essential to pour the product in through an external opening as an operator wearing a gas mask could distribute the pellets or porous discs on the floor, then go out and close the door. At the end of the cycle, opening the two doors allowed efficent natural ventilation. From 22nd June to the beginning of November 1944, it was used as a homicidal gas chamber for groups of about 100 people. Zyklon-B being poured in through a small opening of 15 cm diameter in the roof, a system apparently introduced on the advice of SS Lieutenant Colonel Rudolf Hoess, former commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau and at that time head of Department D1 of the WVHA-SS (SS Economic Administration Head Office). While the history of this gas