|

|

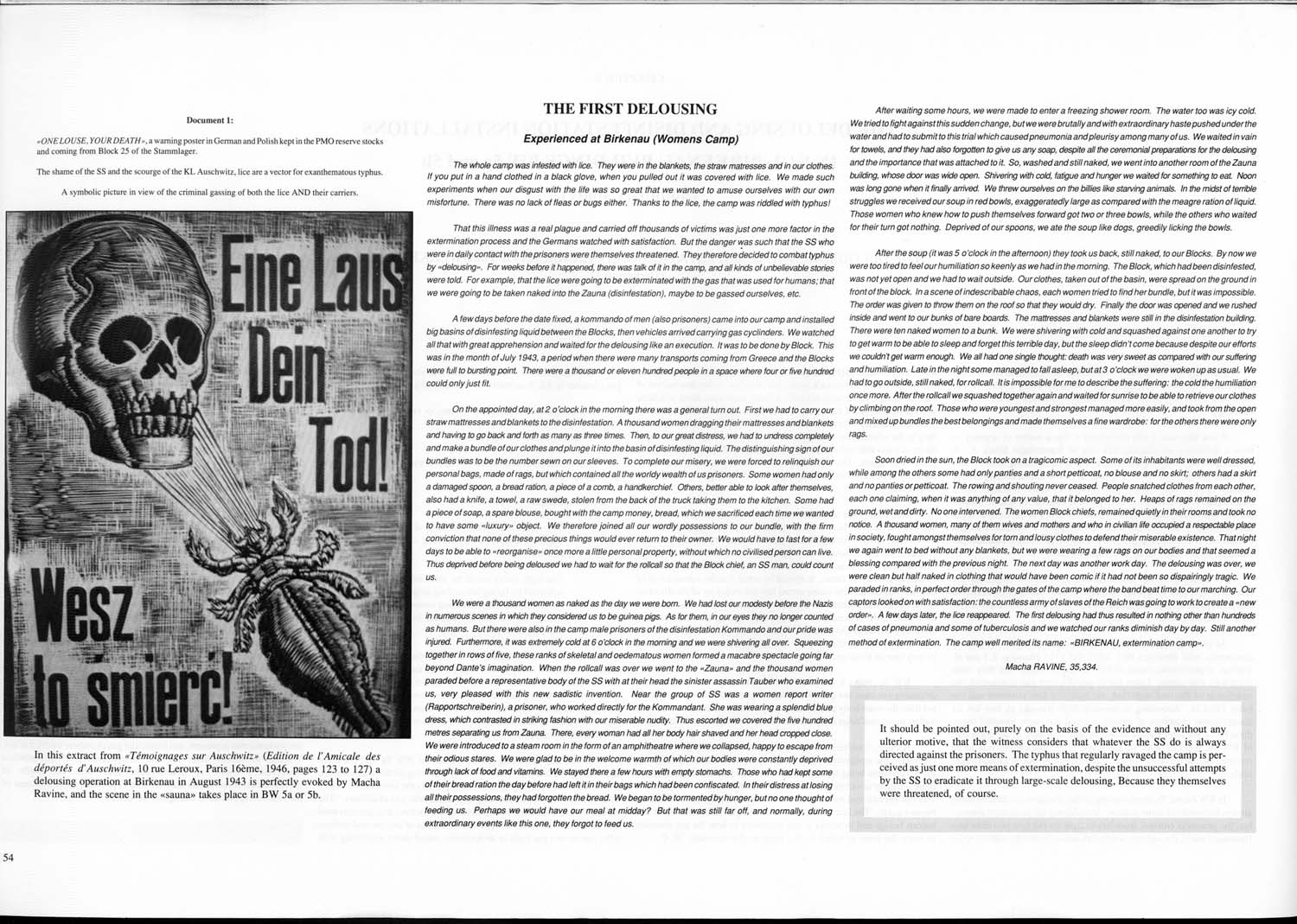

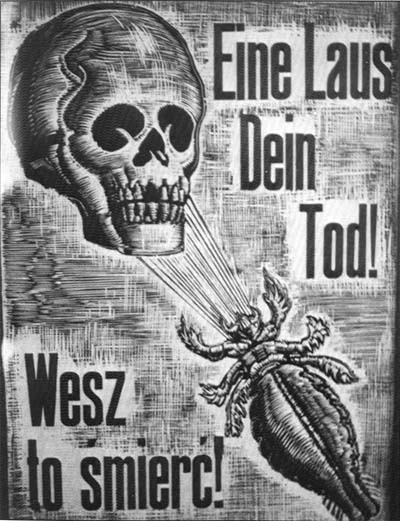

||||

| In this extract from “Témoignages sur Auschwitz” (Edition de l'Amicale des déportés d'Auschwitz, 10 rue Leroux, Paris 16ème, 1946. pages 123 to 127) a delousing operation at Birkenau in August 1943 is perfectly evoked by Macha Ravine, and the scene in the “sauna” takes place in BW 5a or 5b. | |||||

|

|||||

| “The whole camp was infested with lice. They were in the blankets, the straw mattresses and in our clothes. !f you put in a hand clothed in a black glove, when you pulled out it was covered with lice. We made such experiments when our disgust with the life was so great that we wanted to amuse ourselves with our own misfortune. There was no lack of fleas or bugs either. Thanks to the lice, the camp was riddled with typhus! “That this illness was a real plague and carried off thousands of victims was just one more factor in the extermination process and the Germans watched with satisfaction. But the danger was such that the SS who were in daily contact with the prisoners were themselves threatened. They therefore decided to combat typhus by 'delousing.' For weeks before it happened, there was talk of it in the camp, and all kinds of unbelievable stories were told. For example, that the lice were going to be exterminated with the gas that was used for humans; that we were going to be taken naked into the Zauna (disinfestation), maybe to be gassed ourselves, etc. “A few days before the date fixed, a kommando of men (also prisoners) came into our camp and installed big basins of disinfesting liquid between the Blocks, then vehicles arrived carrying gas cylinders. We watched all that with great apprehension and waited for the delousing like an execution. It was to be done by Block. This was in the month of July 1943, a period when there were many transports coming from Greece and the Blocks were full to bursting point. There were a thousand or eleven hundred people in a space where four or five hundred could only just fit. “On the appointed day, at 2 o'clock in the morning there was a general turn out. First we had to carry our straw mattresses and blankets to the disinfestation. A thousand women dragging their mattresses and blankets and having to go back and forth as many as three times. Then, to our great distress, we had to undress completely and make a bundle of our clothes and plunge it into the basin of disinfesting liquid. The distinguishing sign of our bundles was to be the number sewn on our sleeves. To complete our misery, we were forced to relinquish our personal bags, made of rags, but which contained all the worldy wealth of us prisoners. Some women had only a damaged spoon, a bread ration, a piece of a comb, a handkerchief. Others, better able to look after themselves, also had a knife, a towel, a raw Swede, stolen from the back of the truck taking them to the kitchen. Some had a piece of soap, a spare blouse, bought with the camp money, bread, which we sacrificed each time we wanted to have some 'luxury' object. We therefore joined all our wordy possessions to our bundle, with the firm conviction that none of these precious things would ever return to their owner. We would have to fast for a few days to be able to'reorganise' once more a little personal property, without which no civilised person can live. Thus deprived before being deloused we had to wait for the rollcall so that the Block chief and SS man, could count us. “We were a thousand women as naked as the day we were born. We had lost our modesty before the Nazis in numerous scenes in which they considered us to be guinea pigs. As for them, in our eyes they no longer counted as humans. But there were also in the camp male prisoners of the disinfestation Kommando and our pride was injured. Furthermore, it was extremely cold at 6 o'clock in the morning and we were shivering all over. Squeezing together in rows of five, these ranks of skeletal and oedematous women formed a macabre spectacle going far beyond Dante’s imagination. When the rollcall was over we went to the 'Zauna' and the thousand women paraded before a representative body of the SS with at their head the sinister assassin Tauber who examined us, very pleased with this new sadistic invention. Near the group of SS was a women report writer (Rapportschreiberin), a prisoner, who worked directly for the Kommandant. She was wearing a splendid blue dress, which contrasted in striking fashion with our miserable nudity. Thus escorted we covered the five hundred metres separating us from Zauna. There, every woman had all her body hair shaved and her head cropped close. We were introduced to a steam room in the form of an amphitheatre where we collapsed, happy to escape from their odious stares. We were glad to be in the welcome warmth of which our bodies were constantly deprived through lack of food and vitamins. We stayed there a few hours with empty stomachs. Those who had kept some of their bread ration the day before had left it in their bags which had been confiscated. In their distress at losing all their possessions, they had forgotten the bread. We began to be tormented by hunger, but no one thought of feeding us. Perhaps we would have our meat at midday? But that was still far off, and normally, during extraordinary events like this one, they forgot to feed us. “After waiting some hours, we were made to enter a freezing shower room. The water too was icy cold. We tried to fight against this sudden change, but we were brutally and with extraordinary haste pushed under the water and had to submit to this trial which caused pneumonia and pleurisy among many of us. We waited in vain for towels, and they had also forgotten to give us any soap, despite all the ceremonial preparations for the delousing and the importance that was attached to it. So, washed and stilI naked, we went into another room of the Zauna building, whose door was wide open. Shivering with cold, fatigue and hunger we waited for something to eat. Noon was long gone when it finally arrived. We threw ourselves on the billies like starving animals. In the midst of terrible struggles we received our soup in red bowls, exaggeratedly large as compared with the meagre ration of liquid. Those women who knew how to push themselves forward got two or three bowls, while the others who waited for their turn got nothing. Deprived of our spoons, we ate the soup like dogs, greedily licking the bowls. “After the soup (it was 5 o'clock in the afternoon) they took us back, still naked, to our Blocks. By now we were too tired to feel our humiliation so keenly as we had in the morning. The Block, which had been disinfested, was not yet open and we had to wait outside. Our clothes, taken out of the basin, were spread on the ground in front of the block. In a scene of indescribable chaos, each women tried to find her bundle, but it was impossible. The order was given to throw them on the roof so that they would dry. Finally the door was opened and we rushed inside and went to our bunks of bare boards. The mattresses and blankets were still in the disinfestation building. There were ten naked women to a bunk. We were shivering with cold and squashed against one another to try to get warm to be able to sleep and forget this terrible day, but the sleep didn’t come because despite our efforts we couldn’t get warm enough. We all had one single thought: death was very sweet as compared with our suffering and humiliation. Late in the night some managed to fall asleep, but at 3 o'clock we were woken up as usual. We had to go outside. still naked, for rollcall. It is impossible for me to describe the suffering: the cold the humiliation once more. After the rollcall we squashed together again and waited for sunrise to be able to retrieve our clothes by climbing on the roof. Those who were youngest and strongest managed more easily, and took from the open and mixed up bundles the best belongings and made themselves a fine wardrobe: for the others there were only rags. “Soon dried in the sun, the Block took on a tragicomic aspect. Some of its inhabitants were well dressed, while among the others some had only panties and a short petticoat, no blouse and no skirt; others had a skirt and no panties or peticoat. The rowing and shouting never ceased. People snatched clothes from each other, each one claiming, when it was anything of any value, that it belonged to her. Heaps of rags remained on the ground, wet and dirty. No one intervened. The women Block chiefs, remained quietly in their rooms and took no notice. A thousand women, many of them wives and mothers and who in civilian life occupied a respectable place in society, fought amongst themselves for torn and lousy clothes to defend their miserable existence. That night we again went to bed without any blankets, but we were wearing a few rags on our bodies and that seemed a blessing compared with the previous night. The next day was another workday. The delousing was over, we were clean but halt naked in clothing that would have been comic if it had not been so despairingly tragic. We paraded in ranks, in perfect order through the gates of the camp where the band beat time to our marching. Our captors looked on with satisfaction: the countless army of slaves of the Reich was going to work to create a 'new order.' A few days later, the lice reappeared. The first delousing had thus resulted in nothing other than hundreds of cases of pneumonia and some of tuberculosis and we watched our ranks diminish day by day. Still another method of extermination. The camp well merited its name: 'BIRKENAU, extermination camp.'”

|

|||||

| It should be pointed out, purely on the basis of the evidence and without any ulterior motive, that the witness considers that whatever the SS do is always directed against the prisoners. The typhus that regularly ravaged the camp is perceived as just one more means of extermination, despite the unsuccessful attempts by the SS to eradicate it through large-scale delousing, because they themselves were threatened, of course. | |||||