Review

A Memoir of Globaloney, Orwellianism and Dead Sea Fruit

JAMES J. MARTIN

- PERPETUAL WAR FOR PERPETUAL PEACE: A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF THE FOREIGN POLICY OF FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT AND ITS AFTERMATH. Edited by Harry Elmer Barnes, with the collaboration of William Henry Chamberlin, Percy L. Greaves, Jr., George A. Lundberg, George Morgenstern, William L. Neumann, Frederic R. Sanborn, and Charles Callan Tansill. Second, expanded edition, Torrance, California: Institute for Historical Review, 1982. Xvi+ 723 pp., $11.00 paperbound, ISBN 0-939484-01-3

I first saw Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace in the form of long galley sheets draped over the back of a chair in the study of Harry Elmer Barnes’s spread, “Stonewood,” overlooking Lake Otsego, a few miles above Cooperstown, N.Y. A few months later in the fall of 1953 it was published by Caxton Printers of Caldwell, Idaho. To say that it caused delight among revisionists and consternation and outrage among Establishmentarians is a most subdued relation. When Professor Bernard C. Cohen of Princeton University started his review of Perpetual War in the American Political Science Review with the sentence, “This is an unpleasant book to read,” he uttered about the most neutral words regarding the book that one might have read in the estimates made by the official defenders of the Roosevelt faith in those turbulent days 30 years ago. The majority of reviews were notable for their incensed and abusive tone, making the long-observed mistake of confusing generalized snarling with criticism.

That it has taken thirty years for it to reappear, in this new Institute for Historical Review edition, is a commentary on a number of things taking place in our land. One thing can be said of its current form: it at last is in the shape it was intended to be initially by its editor Barnes, with the addition of an originally suppressed chapter by him, about which more later. However, the wide distribution of the original edition, its many reviews and its inclusion in so many bibliographies over the last generation call not for a conventional review but for an assessment of the history of the three decades which have elapsed since the original edition, while calling attention to its contents for the benefit Of a generation just now making its first acquaintance with this basic foundation work of revisionism as it developed, historically, in this country.

Like subsequent verses of well known songs, not many even of those well acquainted with this book recall or remember its subtitle: A Critical Examination of the Foreign Policy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and its Aftermath. That is the subject of the book, undertaken by its editor, Barnes, who wrote three of its chapters, assisted by Charles Callan Tansill, who wrote two, and six others participating in the symposium, who produced the remaining six. I often regret that political and other circumstances prevailing prevented it from being a two-volume set. Though its inspiration and supplier of its main title, Charles A. Beard, had died five years earlier, there were about the land sufficient members of the revisionist fold to have made a companion volume equally significant; the additional contributions of, say, John T. Flynn, C. Hartley Grattan, George Hartmann, Clyde R. Miller, William B. Hesseltine (I wonder what ever happened to Bill’s work on Cordell Hull?), Fred A. Shannon (a chapter by him on the imbecilities of the wartime economy would have been a hilarious interlude in this somber tale), Francis Neilson and Harry Paxton Howard, would have induced utter disintegration among the brigade of critics who found the one book simply unbearable. But it was not to be, even if some of this latter contingent did get in their say in other works.

In looking back on this book across the 30 years between editions, it is necessary to pay attention to the kind of world existing when it was put together. The various authors worked on the essays in Perpetual War mostly between 1951 and early 1953, a time of immense agony in the U.S.A. It was the time of the doleful Korean war, the shooting stage of which ended a bare three months prior to publication. It was a time when the high hysteria and megalomania of World War Two “victory” finally rubbed off, and the boasting and posturing of 1945-50 finally was eclipsed by the reality of another war undertaken under circumstances quite removed from those which eventuated after December 7, 1941. It was not a case of jumping into someone else’s war with the guidelines all drawn and the odds already determined. It was not the nice comfortable adventure in comradeship with an overwhelming coalition of world power and people and with resources so stacked in their favor that the wonder was that any war at all lasted more than a year. (Americans rarely undertook any campaign in the Pacific, for example, without manpower superiority of 3-1 or 4-1, against an antagonist with hardly any raw material resources and virtually no sources of energy.)

The Korean conflict was something else, begun from scratch in June, 1950 under the auspices of the United Nations, the then five-year-old mutual insurance company put together in imitation of the defunct League of Nations created in 1919-21, but with important new designated functions which seemed to commit it in perpetuity to sending its armed bands a la the scalping parties of 1941-45 to put down political sin wherever it might surface in the world. It was this looming function emerging out of the organizing sessions of 1945-48 which had induced Beard to remark about the UNO’s goal apparently being the guaranteeing of perpetual peace by fighting perpetual wars to achieve it, an absurd juxtaposition that appealed to Barnes’s sense of humor as well as seeming to be quite an accurate analysis of the situation, leading to its adoption as the title of the symposium.

The Korean war was no joke, an anyone who saw combat in this ugly, dreary, repelling struggle can tell you. But it was a complicated conflict, probably the earliest Orwellian skirmish, fought on several levels, but with little visibility for most of them. It undoubtedly had far more tangible results on the home front, quite as Orwellian wars are fought to achieve, but not all of these were expectable or desirable. A backlash caused by Americans finding out that they were almost the only ones involved in the “United Nations” war against the massed Communists of the eastern extremities of Asia where China, Korea, Manchuria and Siberia came together, accelerated an anti-Communist ferreting-out program which grievously disturbed the in-place totalitarian liberal Establishment responsible for getting the country involved in it. The war in Asia, appearing more doleful by the month in that it appeared to promise an everlasting slogging across the immense reaches of East Asia in pursuit of an objective lost right at the start, provoked massive unhappiness with the state of politics on every level.

The domestic search for Communists in places high and low alike was intimately related to this absence of military success the stacked scene of World War Two had encouraged all to expect all the time. Another consequence of this rattled state of the public mind was the encouragement of study about how these sorry situations had come to pass, and one of the beneficiaries of this psychic condition was revisionism. Overwhelmed in the first few years of national euphoria after “victory” in 1945, when few wanted to hear anything but “positive” things about the latest Great Crusade, revisionism made a sharp gain in these days of national dolors in the early '50s, and one of its emanations was this book, as Americans began to taste the Dead Sea fruit of “victory,” and some of the consequences of emerging as the monitor of planetary political behavior, and did not like the flavor one bit.

So it was in the decade of the '50s that the majority of the most influential revisionist books were to appear, powered by these same pressures and owing much of the reason for their birth and modest success to a climate of opinion more ready to listen to the obscured and suppressed reasons for this doleful state of affairs in the body politic, international and domestic. That the struggling and troubled New Order of things was immensely unsure of itself in this decade also contributed to the growth of an audience for the revisionist critics.

To be sure, the country had not got over its addiction to the fierce drug of world-saving. The “fix” of 1917-18 had gone into remission during the subsequent two decades, only to return with even stronger symptoms after 1937 and heightened in 1939. But the participation in the lethal posse from 1941-45 had really strengthened the dependence on the hallucinatory impact of the newest essaying-forth, ridding the planet of new ideological sin under Mr. Roosevelt at a cost, among other items, of several hundred thousand American fives and a quintupling of the national debt. The prospect that this might be exceeded and go on forever starting with the era of Mr. Truman had a depressing impact on this zeal for world political purity, though the spectacle of what a war can do to erase unemployment and blot up the nation’s energies was not entirely lost among even those who deplored other consequences. The half-hearted pursuit of “victory” in Korea, the first of the Orwellian wars, contrasted sharply with the all-out “total victory” effort of 1942-45. Its agonized serpentine crawl across the early 1950s had a domestic counterpart which gravely upset the lot running it however, and the campaign against all varieties of Communists and their transmission belts on the home front, viewed with such horror from the perspective of 30 years later, was thought quite proper and harmonious, when it happened, by a percentage of the community which truly frightened totalitarian liberalism.

A measure of this fright was indicated in a booklet being worked on at the same time Perpetual War was nearing production, published by Barnes under the title The Chickens of the Interventionist Liberals Have Come Home to Roost: The Bitter Fruits of Globaloney. In a letter accompanying a pre-publication copy of what we were to refer to for years as “The Chickens,” Barnes acknowledged my assistance by declaring, “I would dearly love to share the title page of this with you, but it would do you far more harm than good,” a reference to his belief that I had a future in the academic world. I believe it is a good barometer for measuring the ideological climate of the land a generation ago, as well as assessing the state of impact of the early revisionism.

When the restrained and cautious Establishment historian Dr. Louis Morton admitted in the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings two years later that World War Two revisionism was an authentic force to conjure with, perhaps the apogee had been reached in the U.S.A. By that time a potent list of volumes was on the record, including those by Beard, Morgenstern, F.R. Sanborn, Chamberlin, Tansill and Francis Neilson, formidably buttressed by a succession of works by Britons, especially Russell Grenfell’s Unconditional Hatred, the best-seller among revisionist books of the '50s; F.J.P. Veale’s Advance to Barbarism; Montgomery Belgion’s Victors' justice; Victor Gollancz’s two remarkable books on the nightmare the Western “victors” had made out of Germany in the first 4 years of “peace"; Freda Utley’s The High Cost of Vengeance, and the two remarkable books cutting Churchill down to size by Neilson and Emrys Hughes. (Over the years this early sobered assessment of Churchill the great war leader has gone into obscurity while those who warmed up to the confrontation with Stalin and his successors tended to ignore what had happened to Britain and chose to refurbish and re-sell Churchill, simply replacing Germany with the Soviet Union in rephrasing his famous declamatory hokum in the bombastic period of 1938-43, the latter year being the one when Sir Winston first began to indicate he had some political sense. In 1976 Solzhenitsyn remarked that as of that date Britain was about as important or influential in the world as Romania or Uganda. Another Churchill and Britain will have the political importance of Easter Island.)

The mention of Churchill recalls other worldwide political facts of life at the time of the publication of Perpetual War. The throaty blather of “war aims” during the recently concluded planetary war had become much muted by now, and a plaintive whining tempered the continuous outflow of “gee, what a great job we did” wartime histories and memoirs from the lands of the “victors.” Other than doubling the area of the world under Communism there was not much to point toward in the area of achievements except the kangaroo court convictions and killing of limited numbers of enemy leaders, which in fact set a very ominous precedent for the future in that it guaranteed future wars, if fought to the same kind of conclusion as that of 1941-45, might well be fought with unprecedented ferocity and savagery, whatever it might take to avoid defeat and subsequent hanging or shooting as “war criminals.” (Now, contrary to 1939, when no legal code in the world included a category specifically designated as “war crimes,” there were all kinds of them, especially as stipulated in the long, tedious compilations of new “law” in the four Geneva Conventions signed on 12 August 1949, so many parts of which have been violated, or ignored so many times in the 130 wars fought since 1949 that collected together as a single statement the infractions of these four Conventions might exceed in wordage the original Conventions themselves.)

In the area of irretrievably lost war goals of the “victors” however was a most palpable physical one, the immense colonial empires of the British, French, Dutch and others; even the United States targeted the Philippine Islands for “independence.” And China had come under the dominance of Maoist Communism less than a year before the Korean conflict, thus completing the bankruptcy of about all the “Western Allies” had told their populaces the war was being fought for. India was already adrift even before the Communist investment of China, and the prize Dutch and French real estate of Indonesia and Indo-China were departing or about to.

One might argue that in the case of the Philippines, the U.S.A. was about to experience getting out from under an impossible burden, though it had not begun that way. Pearl Buck had remarked in a pre-war issue of Asia magazine that in the early years of the century after America acquired the Philippines, part of the aspirations expressed by some hinged around a standing envy of Singapore, conditioned by the belief that a rival and competitor could be built in the Philippines. But what had been put together in some 40 years was another British West Indies instead, than which there was no worse slum.

In the case of the European powers the losses sustained in East Asia were catastrophic, and they were shortly to be expelled from Western Asia and most of Africa as well. The ear-splitting bellowing about the “One World” during the conflict ending in 1945 had declined to a whisper by the early '50s, and no one helped anyone as the colonial plantations of Asia and Africa went into local or “native” receivership. Few were so indecent as to suggest that the scuttle was a direct consequence of the total debility, exhaustion and indigence which their great “victory” had demanded. But the French did put up a fight for Algeria and for Indo-China (Vietnam), a pair of excruciating affairs during which they howled as though their fingernails were being pulled out, but to no avail. These were two more of the Dead Sea fruit harvested from “victory.”

It had been grand good fun financing and arming an immense civilian guerrilla war against the Germans, 1941-45, all in contravention of the very first article of the Hague Convention of 29 July 1899, and the Annex to this Convention, also signed at The Hague on 18 October 1907. Now, when the “victors” began to experience the very same thing in Asia and Africa, it did not seem anywhere near as pleasant. Even the U.S.A. were to get their share, first against the Hukbalahap Communists in the Philippines, and then for an extended period of time in their ill-fated years in Vietnam, when for a time it looked as though the administrations of three successive Presidents were determined to succeed in the re-colonization of Southeast Asia where the French had failed so miserably. (It now appears that thanks to enlightened new “international law,” future wars will increasingly be fought around and through civilian populations, the massive removal of such populations now being construed a “war crime.")

It is quite possible, it is true, to put a constructive emphasis on the American replacement of France in the fighting in Southeast Asia. Given U.S. military success and a lot of Japanese economic help, South Vietnam might easily have become another South Korea, a prodigious volcanic industrial beehive, contributing to the pouring of more billions of dollars' worth of manufactured goods upon Europe and America, to increase further American unemployment, resentment and social disorder. Of such things does “victory” often consist.

A further case in point, while dealing with possible consequences of unanticipated results which come about from myopic “statesmanship” and gravely aggravated atrophy in the capability to look ahead, is the remarkable series of articles in the London Daily Mail in the last week of November 1982. A near high in hysteria is reached therein as the paper’s Far East reporter, after several weeks in Japan and the other “four dragons” of South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore, witnessing what this Asian production is doing to Britain, the one-time “workshop of the world,” suggests that if anyone in the United Kingdom looks forward to having a job of any kind by the year 2000, then they had better busy themselves in “finding another planet” at their earliest convenience. When the reporter contemplated what would happen in the field of cost and price cutting and competition should mainland China ever chuck their preposterous Communism and join the free enterprise system of the “free world,” he could only summon a profound shudder.

The republication of a 30-year-old book does not call for reviews. They are already part of the record and can be consulted. The purpose of republication, mainly to make the book available to those not born or too young to profit from its information and analyses at the time of original issue, calls for some effort on the part of these new readers in recapitulating the events between the two editions. In this way some rough measure of assessing the validity of the original authors' approach, mustering of facts and conclusions can be made, an effort the readers in 1953 and the years immediately following did not have to make, since they had lived and were still living through the actual times themselves.

This brings up the aspect of the book related to the British novelist George Orwell and his influence on the thinking of Barnes, especially. The latter’s chapter analyzing the early 1950s in terms of Orwell’s nightmare vision of world politics laid out in his novel 1984 deserves special attention, since it was omitted from the 1953 edition and made available to readers old and young alike just recently. This however presents a problem ruminated upon by the hero of Orwell’s tale, Winston Smith, reproduced as an epi-paragraph gracing the first page of Barnes’s Chapter 10. With the passage of sufficient time and given systematic suppression or distortion of the past, it often becomes impossible to estimate the present because there is no reliable standard or picture of previous times against which to measure it. And the problem is not one just facing any given generation in such a place as the Soviet Union or any other Communist land, where constant tailoring of the past to conform to current policy is commonplace and procedurally expectable. What Orwell calls the “Memory Hole” is present everywhere; how diligently and comprehensively it is used to dispose of the inconvenient past is what separates one state from another, and there are none which are not involved in practical applications of it. Today efforts are made to blot out memory of things that happened just a few months or even weeks ago, let alone decades or generations past. Those in charge of the present are always in a position of asserting that things never were better, and given the assistance of sufficient camp-followers specializing in the past, can always come up with a version of what took place to provide the necessary comforting support. It is the republication of books such as Perpetual War which does so much to discommode and annoy the beneficiaries of the New Order. It is for this reason that the essays of William Henry Chamberlin and George Lundberg should also be paid special attention. Neglected 30 years ago, the passage of three decades gives these sober treatments a significance they could not have had in 1953, since we were still too close to it all.

Eventually, the new Establishment steadied and began to assert itself in the euphoric years of the Eisenhower presidency, particularly 1954-60, laying the groundwork for the perfection of an essentially one-party State in regard to foreign policy in the last two decades. The concomitant derailing of revisionism is an integral aspect of this enlarging monolith, despite the recurrence of new crises and in recent years the growth of signs that the whole enterprise is in trouble, globally. But by and large the essential phoniness of the conflict we tend to call the Cold War, generically, can be buttressed with sufficient evidence to make the Orwellian analysis still essentially sound. And one must remember that the central idea in his book was the use of foreign policy to control domestic populations, thus requiring that world conflict be confined to sporadic and very localized encounters, easily terminated if necessary, employed as much as possible to entrench further the entrenched, while simulating endless confrontation. The utter failure to support anti-Soviet uprisings in “East” Germany (read: Central Germany, the East having disappeared behind the western frontier of Poland, after Stalin cut himself in on the eastern 45% of 1939 Poland at Potsdam), Czechoslovakia and Hungary in the 1950s puzzled many in view of the stentorian generalized anti-Communism of regimes both Democratic and Republican in this country. There may have been some connection between this action and the famous wire from Mr. Eisenhower’s Secretary of State to Marshal Tito, the “independent” Red dictator of Yugoslavia in November, 1956 which announced that the U.S. did not favor the establishment of antiSoviet regimes on the borders of the Soviet Union. But we can not get into the strange relationship between the “West” and the “East” these last 38 years at this point without grievously overrunning the space originally allocated to a commentary on a book and its times.

Perpetual War is a work which few settle down to reading at a simple sitting. Its diversity appeals rather to absorption of single chapters and reflection on the implications of their relationships as one goes along. Barnes’s opening gun on the total situation, laying the foundation for the persisting confrontation between the Revisionists and the Establishment, will often be as much as some can deal with in one dose; it is a masterpiece, the result of much re-writing and concentration via several editions of his privately-published brochure, The Struggle Against the Historical Blackout, an early edition of which came my way in the summer of 1948, initiating our first correspondence.

The separate diplomatic history chapters by the late Professors Tansill and Neumann and the Oxford-trained international law scholar and subsequent judge, F.R. Sanborn, have aroused no refutation, but much sputtering and choking on the part of angered paladins of Rooseveltian innocence in foreign affairs, annoyed at this attention to his steady movement toward war while uttering little but the formalized political patter of “peace.” The chapters dealing with the Pearl Harbor tragedy stand to this day as capable of little improvement despite all that has come upon the record in the 30 years since they were published. George Morgenstern’s is an admirable appendix to his 1947 book Pearl Harbor, a volume which should never have been allowed to go out of print. As for the analysis of the nine investigations of Pearl Harbor by Percy Greaves, it is still the only thing of its kind and of inestimable value and utility. If one wants to see in outline the recent book Infamy by John Toland a generation before it was published, one just has to read Greaves’s essay carefully. Reference has already been made to the balance-sheet contributors by Lundberg and Chamberlin. They and the concluding chapters by Barnes may excite someone some day to carry their story forward across the thirty years separating them then from us today. The final result may be well nigh unendurable. It is a landmark occasion and a publishing event to see Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace back again. It is indeed most pleasurable for me to say, “Welcome back!”

|

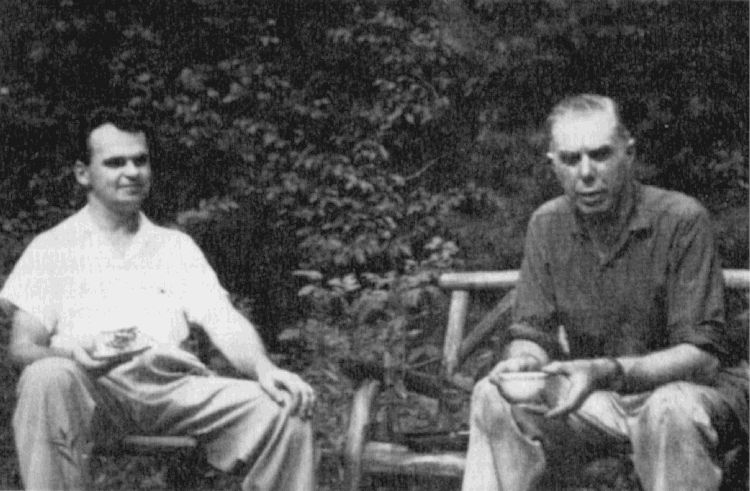

| James J. Martin (left) with Harry Elmer Barnes in the back yard of Barnes’s hunting camp, Redfield, New York, 8 August 1954. |

|---|