Translation:

Charles HERMELINE

ACROSS EUROPE

TRAVEL NOTES

Sanard & Derangeon

174, rue Saint Jacques

PARIS 1898

The women are walking rainbows. Red, blue, green shimmer in their clothing. With a ray of sunshine on these sparkling clothes the main square offers the spectator a veritable orgy of bright colors. All around Sukiennice, a sort of museum-treasurehouse-bazar that occupies the center, there is a multicolored teeming that recalls one of our flowering meadows agitated by the wind. But here the flowers are alive, they rush about, they come and go, and in the middle of them, almost immobile, like the scarecrows that stand in our fields, the black figures of the Jews.

They form a very curious population, these, Cracow Jews. Without doubt, all the Polish Jews are worth seeing. But in Russia they are subject to more control.

It is in Galicia that the Polish Jew is seen in all his native filth, and also at his most picturesque.

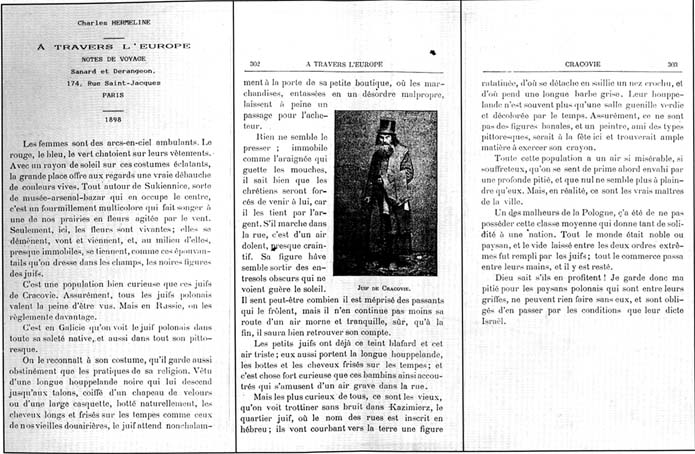

He can be recognized by his dress, to which he clings as obstinately as to the practices of his religion. Wearing a lone, black coat, reaching to his feel, a felt hat or a large cap, boots of course, his hair, long and curled over the temples like that of our old dowagers. The Jew waits nonchalantly at the door of his little shop, where the goods, heaped up in slovenly disorder, hardly leave room for the customer to move.

Nothing seems able to make him hurry; immobile as the spider waiting for a fly, he knows that the Christians will be forced to come to him, for he holds them through money. If he walks in the street, it is with a mournful, almost fearful air. His wan face seems to have emerged from a dark basement that scarcely sees the sun. He perhaps feels how much he is despised by those who brush by him, but he nevertheless continues on his way with a mournful quiet air, certain that in the end he will do well out of it.

Jewish children already have this pale complexion and mournful air; they too wear the long coat and boots and have their hair curled over the temples. And it is a very curious thing that youngsters so attired play gravely in the street.

The most curious of all, however, are the old men who can be seen scurrying silently about in Kazimierz, the Jewish quarter, where the names of the roads are inscribed in Hebrew; they turn towards the ground a wizened face, from which juts a hooked nose and hangs a long, grey beard. Their coat is often no longer anything but a dirty greenish rag, faded by age They are certainly no ordinary figures, and a painter, fond of picturesque types, would be in his element here and find ample material to exercise his pencil.

All this population has such a miserable air, so sickly, that at first one is overcome by a feeling of deep pity, and none seem more deserving of sympathy than they. But in reality they are the true masters of the town.

One of Poland’s misfortunes has been not to have the middle class that gives so much solidity to a nation. Everybody was either a noble or a peasant, and the space between these two extremes was filled by the Jews. All trade passed into their hands, and has remained there.

God knows that they take advantage of it! I therefore save my pity for the Polish peasants who are in their clutches and can do nothing without them, and are obliged to accept the conditions dictated to them by Israel.

Illustration caption: “A Cracow Jew”