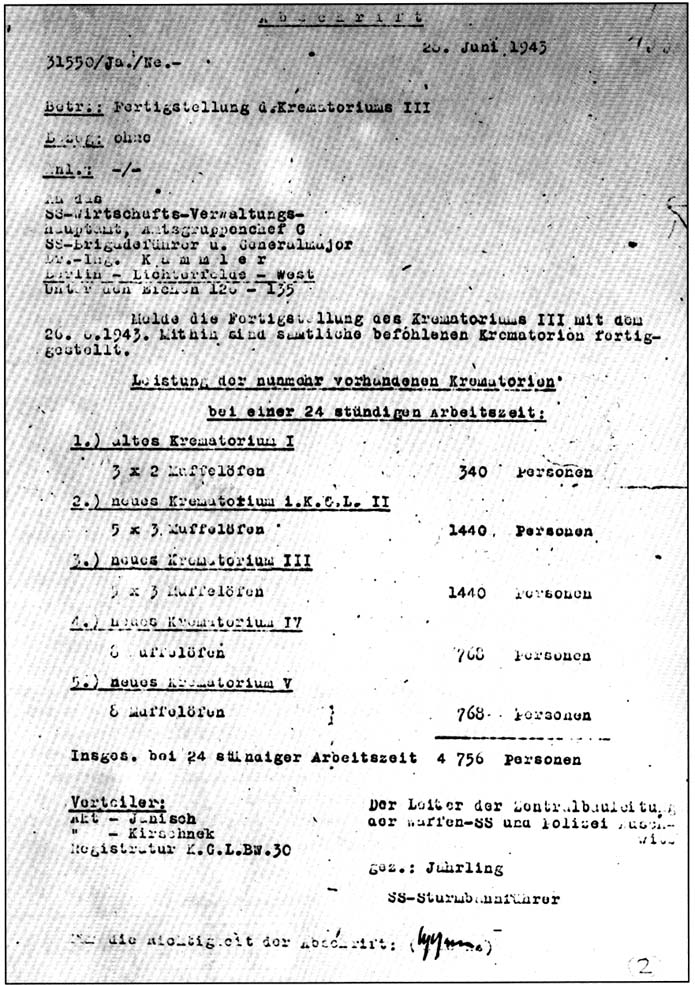

Document 68

[PMO file BW 30/42 page 2 and Archiv Domburg (GDR) ND 4586] |

|

|

On Monday 13th September. Kirschneck wrote up a summary of the sometimes heated discussions of 10th and l1th [Document 69 and 69a]. In this summary he formally stated that PRÜFER HAD BEEN CONSULTANT FOR THE WHOLE INSTALLATION IN SUMMER 1942 [i.e. for the four new Krematorien], This was already apparent from previous correspondence, but had never been spelled out so clearly before. Despite the “amicable arrangement” that had been arrived at, i.e. equal division of the cost of repairing the chimney between the three parties, a solution that was in fact to Prüfer’s advantage, the report makes it clear that relations between Prüfer and the Bauleitung, which had been excellent in the second half of 1942, had deteriorated and were becoming rather bad. The SS were blaming him for the building of two useless Krematorien (a waste of 400,000 RM) and for the problems with the chimney of Krematorium II.

On 28th September, Kirschneck sent a registered letter to Messrs Robert Koehler, announcing that the cost of creating the lining of the chimney in fact amounted to 4500 RM, so that the firm owed 1,500 RM [which meant that Koehler had worked on this job simply for the glory, their profit having gone up in smoke] and that the final account would be sent shortly. In addition, the SS informed Koehler that the Bauleitung had once again urgently requested the latest drawing of the chimney [probably concerned with the consolidation or relining of the underfloor flues] which Topf had been promising to dispatch without fail for TWO MONTHS already (since the end of July 1943) [PMO file BW 30/34, page 16] |

[What happened after this. i.e, whether or not the repairs were carried out, and if so whether by Topf or Koehler, is not known. If it was done, the job would have been extremely difficult and unpleasant, for the bricklayers would have had to work lying down in flues 50 cm wide and 70 cm high, which seems to be at the limits of the possible. Alternatively, the flues could have been reached from above, but this would have meant demolishing one third of the concrete floor of the ground floor of the Krematorium, which does not seem to have been done. In any event, if the work was done, it would have been in October 1943 and the furnace would have had to be shut down for considerable time. So in the second half of 1943, Krematorium II was out of service for two to three months for sundry repairs. As for the Krematorium III chimney, of the same design as that of Kr II, it is not known whether similar problems were encountered, also causing that Krematorium to be shut down for a while, as the available files have nothing to say on the subject. The sudden and permanent shutdown of Krematorium IV, the gradual shutdown of V and the temporary shutdown of II, are again in line with the coke delivery figures for the four Krematorien from March to the end of October 1943, which indicate an average rate of only just sufficient to keep one Krematorium of type II/III in full operation.]

|

In late September and early October 1943, Huta produced the regularization drawings for Krematorien II and III. The first, sheet 12 (not known today), was drawn on 20th September, then followed on 21st 13a, 23rd 14a, 24th 15 and finally, on 9th October. 16a [see these drawings in annex].

On 2nd November 1943, Huta sent the Bauleitung the final accounts for their work on Krematorien II and III. The next day, they sent a registered package to complement these accounts, containing three copies of more of their drawings for the two buildings, sheets 13, 14, 15 and 16 of project 109 [7015/IV].

On 6th November. following a conversation between Camp Commandant Hoess and Bischoff (who had just been appointed Head of the Silesian Waffen SS and Police Construction Inspectorate and replaced as head of the Auschwitz Bauleitung by SS Lieutenant Werner Jothann, a building technician), a letter was written for the Bauleitung by SS Sergeant Kamann (responsible for gardening and a photographer), requesting SS Major Joachim Caesar, head of the agricultural section of the camp, to supply various trees to surround Krematorien II and III (referred to as I and II) [Document 70]. This ring of greenery was intended more to make the Krematorium sites look agreeable than to camouflage them, as was mistakenly thought for a long time. Judging by what was actually planted (as against the 300 trees and 500 bushes planned for each Krematorium) and where it was planted, half way between the buildings and the surrounding barbed wire fences [Document 71], the aim was clearly more to reassure future victims with a calm rural décor than to try to hide a criminal activity known throughout the camp. What is more, because of a lack of plants, the implementation of the plan was very late (1944) and was limited to a very thin ring, scarcely visible [Document 72] and incomplete [Document 73], with small trees (the diameter of whose trunks was no more than five centimeters in 1945 [Document 71]) and the creation of a formal garden in the north yard of Krematorium II, perfectly visible on the aerial photograph of 25th August 1944 and found intact at the Liberation [Document 74]. |

[This letter, often cited by traditional historians, is the basis of the myth of the “Tarnung / camouflage” of the Krematorien. Thanks to the concept of “camouflaging” the means by which the most criminal aspect of the Third Reich was implemented, certain historians seem to have considered themselves authorized to make quite unjustifiable generalizations. The use of “camouflage” enabled them to replace scant knowledge by certainty and brought dangerous by confused thinking. A suspect installation was “criminalized” by the introduction of “camouflage”. A shower room was or a disinfection gas chamber could be a camouflaged homicidal gas chamber. If the documents found proved that the suspect installation was in fact used normally for its stated purpose, then the second aspect of “camouflage” came into play, “coding”, an indispensable complement in certain writings. The document mentioning normal use, according to this argument, must be “in code”, because it referred to a “camouflaged” place. Thus the word “Leichenkeller 1” [corpse cellar 1] in Birkenau Krematorien II and III “encoded” the homicidal gas chamber function, and “Leichenkeller 2” encoded the undressing room function (one wonders what “Leichenkeller 3” would have encoded, if, unfortunately, it had not been split up into perfectly clearly designated rooms). This historical “methodology”, all the more intransigent because it was ignorant, stood in the way of any objective research, because being ignorant of the chronological and architectural evolution or even the practical arrangement of the premises, it had taken the easy way out. The theory of “camouflage-coding” was further reinforced by a third concept, the last of the trilogy. that of “secret”, which made it possible to hide gaps in one’s own knowledge by blaming the “secrecy” supposedly practiced by those to be denounced. In fact the extermination of the Jews was such an open secret that in 1943-44, train passengers going through Auschwitz station in daytime crowded to the windows to better see where the Jews were being liquidated, and at night they saw Birkenau brilliantly lit by the thousand lamps of its perimeter fence. What they did not know, and this was the only “secret”, was the method used by the SS.

|

|