The Holocaust Revisited A retrospective analysis of the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination complex

New photointerpretation illuminates a grim chapter of history.

By Dino A. Brugioni and Robert G. Poirier (CIA)

cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/vol44no4/html/v44i4a06p_0001.htm

UNCLASSIFIED

This publication is prepared for the use of U.S. Government officials, and the format, coverage, and content are designed to meet their specific requirements. U.S. Government officials may obtain additional copies of this document directly or through liaison channels from the Central Intelligence Agency.

The authors have been strong advocates of the application of aerial photography to historical research and analysis. [*] Our convictions about the utility of this medium to the professional historian have been strengthened as we became increasingly aware of the many historical problems to which the exploitation of aerial photography can contribute an added dimension. In this paper, we attempt to demonstrate the application of aerial photography to a historiographical problem.

Our interest in the subject of Nazi concentration camps was rekindled by the television presentation “Holocaust.” In the more than thirty years since VE Day, 8 May 1945, much has happened to these camps. Some, like Treblinka, have been completely obliterated; others, such as Dachau and Auschwitz, have been partially preserved as memorials.

Aerial reconnaissance was an important intelligence tool and played a significant role in World War II. We wondered whether any aerial photography of these camps had been acquired and preserved in government records. If imagery was available, we thought it likely that the many sophisticated advances in optical viewing, and the equipment and techniques of photographic interpretation developed at the National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC) in recent years would enable us to extract more information than could have been derived during World War II.

We had a number of advantages not available to the World War II photographic interpreters. Instead of 7X tube magnifiers, we had micro-stereoscopes. Our modern laboratory photo-enlargers were vastly superior to those available to earlier interpreters. While the World War II photointerpreter performed his analysis by examining paper prints, we would use duplicate film positives allowing detailed examination of any activity recorded on the film. The present day imagery analyst also has the advantage of years of training and experience, while the World War II photointerpreter was extremely limited in both. Most importantly, for this project, we have the advantage of hindsight and abundant eyewitness accounts and investigative reports on these camps. [1] We therefore had the opportunity to study the subject from a unique perspective.

We faced two immediate problems as we began our investigation. We knew that the cameras carried by World War II reconnaissance aircraft were limited to about 150 exposures of Super-XX Aerocon film per camera and that this film resolved about 35 lines per millimeter. The film was exposed at “point” rather than “area” targets which were selected for their strategic or tactical importance. Thus, when the reconnaissance aircraft approached the target, the pilot or aerial photographer would switch on the cameras shortly before reaching the target and then turn them off again as soon as the target was imaged. There was nothing like the broad area coverage which modern photoreconnaissance makes available to the photo researcher. To find photos of a concentration camp, therefore, we would have to identify one which was located close to a target of strategic interest.

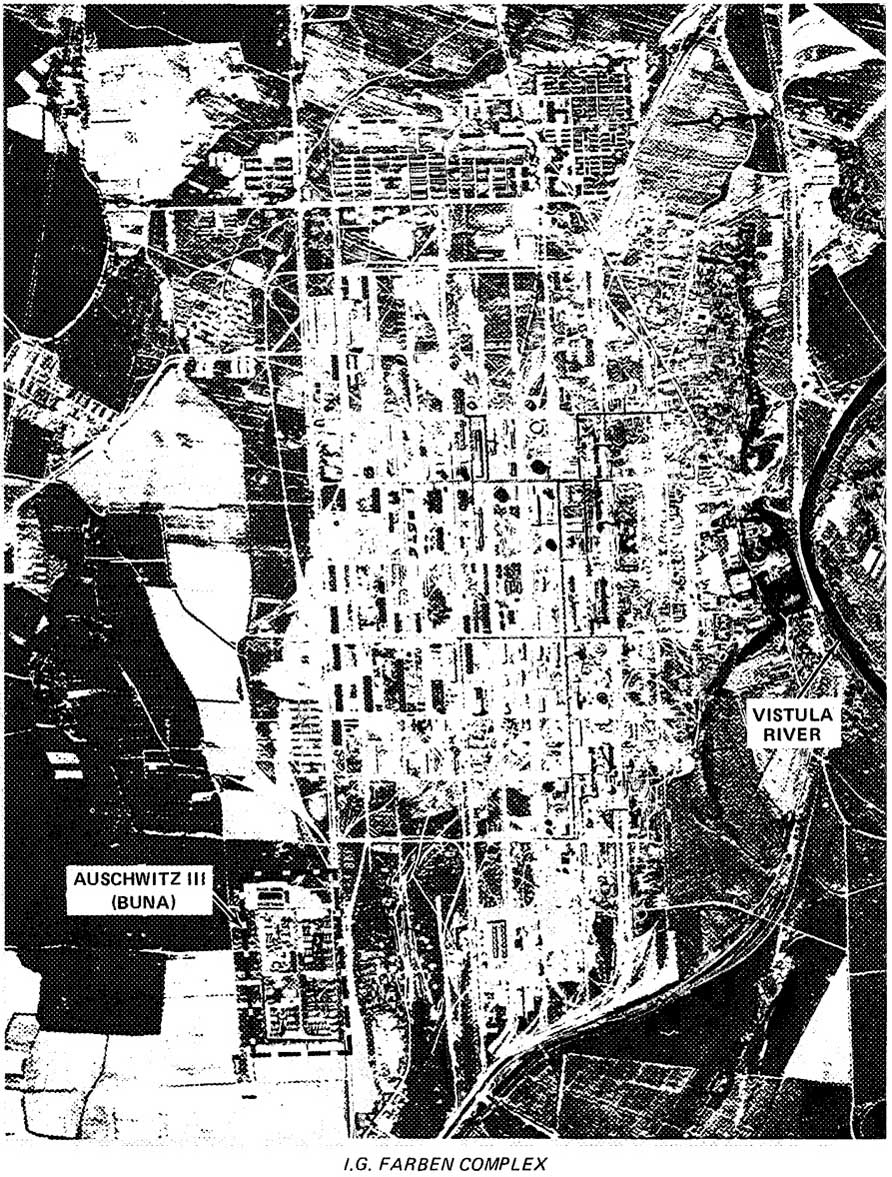

Since the Nazi concentration camp system was so widespread, we also had the immediate chore of narrowing the scope of the investigation to manageable proportions. Our research revealed that the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination complex was only 8 kilometers from a large I. G. Farben synthethic oil and rubber manufacturing facility. We knew that oil and rubber production plants were high on the Allied bombing list. Auschwitz, then, in addition to providing us with a high degree of name recognition, offered a strong probability of having been filmed as a by-product of tactical reconnaissance. Our research soon produced positive results.

The Defense Intelligence Agency, which is the custodian of World War II aerial reconnaissance records, was given the coordinates for Oswiecim (Auschwitz), Poland, through NPIC’s film distribution and control center. DIA ran a computer search against the coordinates within the time frame we had selected and produced a printout of all the unclassified photographic references to film stored in the National Archives' records center at Suitland, Maryland. From this list we were able to order the photography we desired sent to NPIC for photographic analysis. On off-duty hours, we examined all the available unclassified aerial imagery for evidence of the Holocaust at Auschwitz.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau Extermination Complex

The Auschwitz-Birkenau complex had its origins in spring 1940. A concentration camp was organized in a former military camp in the suburbs of Oswiecim (Auschwitz), Poland. When the first trainload of German criminal prisoners arrived in June 1940, it marked the beginning of a system which would eventually total some 39 subsidiary camps and make the name of Auschwitz synonymous with terror and death. [2]

In the fall of 1941, the Auschwitz concentration camp entered the most sinister phase of its expansion with the construction of a camp on the moors of Brzezinka (Birkenau). Under cover of a prisoner of war camp, it would become a center for Sonderbehandlung, i.e., “Special Treatment,” the Nazi codeword for extermination. During the following three and one-half years, an estimated two to three and one-half million people would meet their deaths on this remote Polish moor.

Details of the horrors perpetrated at Auschwitz have been reported many times and at length. It is not our purpose to reiterate that type of detail but rather to see if any of that activity had been recorded by the World War II aerial reconnaissance cameras.

Auschwitz is located in a remote area southwest of Warsaw on the Krakow-to-Vienna rail line. We found no evidence of any Allied reconnaissance effort in the Auschwitz area prior to April 1944. On 4 April 1944, an American reconnaissance aircraft approached the huge I. G. Farben facility for the first time.

The format employed in the balance of this paper will present the background information for a particular topic and then a photographic analysis of the pertinent imagery. All available imagery on Auschwitz acquired between 4 April 1944 and 21 January 1945 was examined.

Background: Construction of the various Auschwitz camps began in spring 1940. Auschwitz I, the so-called Main Camp, was operational by fall of that year. The development of Birkenau (Auschwitz II), began in fall 1941 with Russian prisoners of war as construction crews. The I. G. Farben industrial facility, referred to as “Bung” (Auschwitz III), was begun at Monowice in April 1941. Expansion of these facilities was virtually continuous until the evacuation of the area by the Nazis in January 1945. The operation of these vast petrochemical facilities was a joint SS and I. G. Farben venture. Farben had full access to a source of slave labor-prisoners from Auschwitz and local British prisoners of war-and the SS received the salaries paid their prisoners.

Crippling the German petrochemical production system was a high Allied priority, so the targeting of the Farben complex was inevitable. The late date of the reconnaissance effort is probably attributable to the plant’s production status; it produced no significant amounts of fuel until 1944. Another factor was probably the distance from Allied air bases — about 750 miles from England and 700 miles from Italy.

The mission of 4 April 1944 produced very little photographic coverage of the I. G. Farben complex. It was not until the 26 June 1944 mission (Photos 1 & 1A) that an overall view of the complex, both as to extent and purpose, could be interpreted. For our study, however, even the partially successful mission of 4 April provided positive evidence.

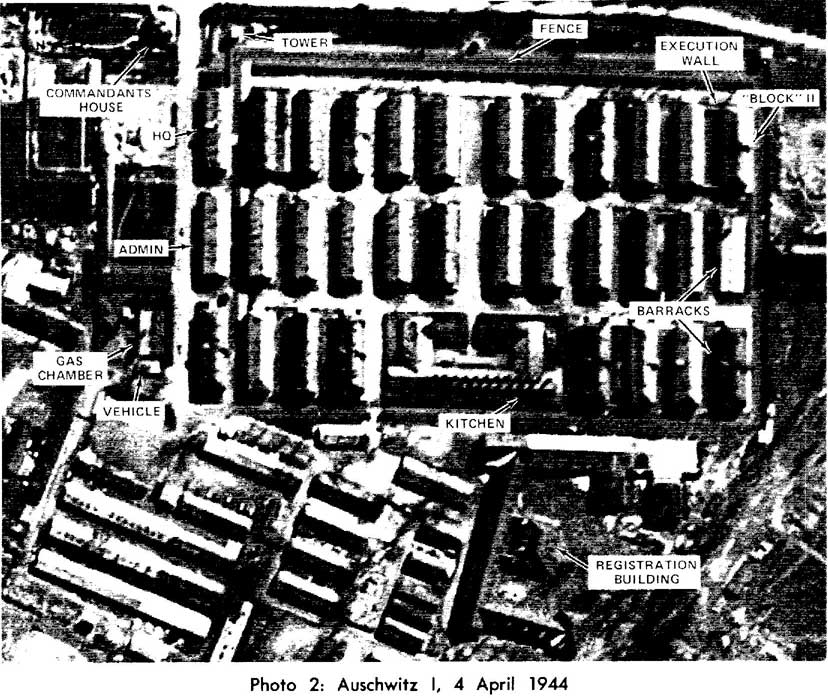

Auschwitz I

Background: Details of the origin of the camp have been outlined earlier, but some additional comments are appropriate. It was at this facility that experiments in mass extermination by using Zyklon B gas were first carried out. Rudolf Hoess, the notorious camp commandant, initially tested the use of that gas on Russian prisoners of war in 1941. The first gas chamber and crematorium, number I by the Nazi numbering system, was later constructed at this camp. The Main Camp penal barracks for problem prisoners (Barracks Block 11), and the medical experimentation barrack located here would both become infamous.

Photo Evidence: Analysis of the facilities at Auschwitz I (Photo 2) combined with the collateral information, corroborate eyewitness accounts of its description. We can identify Gas Chamber and Crematorium I, the Commandant’s quarters, the camp headquarters and administration buildings, the prisoner registration building, the individual barrack blocks and the infamous “execution wall” between barrack blocks 10 and 11. This latter facility was used for the exemplary execution of “problem” prisoners. Death was inflicted either by hanging or shooting against the execution wall. In addition to the above, the camp kitchen, guard towers, and the security fencing can all be identified.

On the photography of 4 April 1944, a small vehicle was identified in a specially secured annex adjacent to the Main Camp gas chamber. Eyewitness accounts describe how prisoners arriving in Auschwitz-Birkenau, not knowing they were destined for extermination, were comforted by the presence of a “Red Cross ambulance.” In reality, the SS used that vehicle to transport the deadly Zyklon B crystals. Could this be that notorious vehicle? While conclusive proof is lacking, the vehicle was not present on imagery of 25 August and 13 September 1944 after the extermination facility had been converted to an air raid shelter. [3]

The preferred method of shipping prisoners to Auschwitz was by rail. Large transports arrived in the railyards of Auschwitz from all sections of Europe. To the west of the camp, as shown in Photo 2, a number of transports are present in the railyard and an additional train is arriving. A new rail spur from the main line into Birkenau is under construction. Eyewitness accounts indicate that work on this spur continued round the clock in anticipation of special shipments of Hungarian Jews in May-July 1944. [4] Some equipment, probably construction gear, appears to be at work on the new spur. It was complete and operational when seen on imagery of 26 June 1944.

Birkenau

Background: Birkenau, the “Birch Wood,” underwent continuous expansion from autumn 1941 until the suspension of the extermination effort in November 1944. As a “Special Treatment” facility, it had a planned capacity of 200,000 prisoners. Had Nazi Germany won the war, evidence presented at the War Crimes Trials revealed that it was destined to be the extermination center for the Czech and Polish nations. [5] The camp contained more than 250 barrack blocks subdivided into sections and some 95 support buildings. Four large gas chambers and crematoria were contructed here in 1943.

Photo Evidence: A 7X enlargement of the 26 June 1944 imagery reveals the camp layout in considerable detail (Photo 3). The rail spur and debarkation point near Gas Chambers I and II are complete. A rail transport is present within Birkenau. The site of the four gas chambers and crematoria can be identified. The locations of the various Birkenau sub-camps, e.g., the “Gypsy Camp,” the “Women’s Camp,” could also be traced. Expansion of the facility into Section III is under way. The SS Headquarters and Barracks complex is seen east of the camp. The security arrangements can be traced in considerable detail.

Several indications of extermination activities can be identified in the camp. Smoke can be seen near the camp’s main filtration facility. While this is to be expected near the camp crematoria, where bodies had to be burned in open pits during the hectic days of the Hungarian Jewish influx, it is a surprise to see it here. There are a number of ground traces near Gas Chambers and Crematoria IV and V which could also be connected with extermination activities. Ground scarring appears to the rear of Gas Chamber and Crematoria IV and is very noticeable to the immediate north and west of Gas Chamber and Crematorium V. These features correlate with eyewitness accounts of pits dug near these facilities; they were no longer present on coverage of 26 July and 13 September 1944. The small scale of the imagery, however, prevents more detailed and conclusive interpretation. [6]

In portions of the imagery not shown in Photo 3, activity in the rail yards, the layout of the surrounding countryside, to include several of the Polish villages forcibly evacuated when the Nazis established Auschwitz, and the marshes south of the camp used for human ash disposal can be identified.

Imagery acquired on 26 July 1944 added little new information to the study. The first evidence of Allied bombing at the I. G. Farben complex and a very large transport of prisoners in Birkenau could be identified. While an overall view of the complex was obtained, the exceptionally small scale of the imagery precluded detailed interpretation.

The Extermination Process

Background: Extermination operations in progress at Birkenau were recorded on aerial photography of 25 August 1944. By that time, rail transports of prisoners were being channeled into Auschwitz from locations throughout occupied Europe in a desperate attempt to achieve the “Final Solution” prior to the collapse of the Nazi war machine. After a trip lasting from a few hours to days, those who survived the journey faced a selection process. SS “doctors” screened the prisoners to determine those fit to be used as slave laborers and those to be exterminated. Those selected as laborers were sent “to the right” while those to be exterminated were sent “to the left,” according to numerous eyewitness accounts of these last tragic moments. [7]

Photo Evidence: A 10X enlargement of imagery acquired on 25 August covers only the southern third of Birkenau and is of very high quality for its day (Photo 4). The imagery illustrates eyewitness accounts of the death process at Birkenau. A rail transport of 33 cars is at the Birkenau railhead and debarkation point. Prisoners can be seen beside the train. The selection process is either under way or completed. One group of prisoners is apparently being marched to Gas Chamber and Crematorium II. The gate of that facility is open and appears to be the destination of that ill-fated group. [8]

Groups of prisoners can be seen marching about the compound, standing formation, undergoing disinfection and performing tasks which cannot be identified solely from imagery. A detailed view of the Women’s Camp and individual barrack blocks was obtained. (Many of the so-called “barracks” provided as living quarters were originally prefabricated stables intended for use in Africa with the Afrika Korps.) We can also identify details of the camp security system-the electrified fences, guard towers, the camp main gate and guardhouse, as well as the special security arrangements around the gas chambers and crematoria.

High quality imagery of the entire Birkenau complex was obtained for the first time on 13 September 1944. A huge transport of some 85 boxcars is present at the Birkenau railhead. Details of the compound, including the expansion into Section III necessitated by the large influx of Hungarian Jews, were observed. [9] A large column of prisoners, estimated at some 1,500 in number, is marching on the camp’s main northsouth road. There is activity at Gas Chamber and Crematorium IV, and its gate is open; this may be the final destination of the newly arrived prisoners.

Registration

Background: Prisoners selected as slave laborers were processed through a registration system which culminated in numbers being tattooed on their arms prior to their being quarantined and assigned to work details.

Photo Evidence: In Auschwitz 1, we have the other part of the drama, those sent to the right,” being enacted at Birkenau (Photo 5). In front of the Main Camp Registration Building, a long line of prisoners is visible. This was undoubtedly the group spared death in the gas chambers but condemned to a living death in an SS work detail. They stand frozen in time, awaiting their tattoos and work assignments.

The Gas Chambers and Crematoria

Background: The gas chambers and crematoria at Birkenau were designed to process some 12,000 people a day. The prisoners sent “to the left” were deceived into thinking they were going to be showered and disinfected. After undressing in an anteroom, they were herded into the shower/gas chamber and put to death by means of Zyklon B gas crystals introduced into the chamber through exterior vents. The bodies were then moved to the crematoria or external burning pits for disposal.

Photo Evidence: The photography of the gas chambers and crematoria in the southern section of Birkenau appear to be historically unique (Photo 6). As far as we have been able to determine, no other photography of these facilities exists. The Birkenau gas chambers were special access facilities, even for most Nazis, and all photography was forbidden. The extermination facilities at the camp were destroyed by the Nazis prior to the camp’s being liberated by the Red Army in January 1945. [10]

We can identify the undressing rooms, gas chambers and crematoria sections as well as the chimneys. On the roof of the sub-surface gas chambers, we can see the vents used to insert the Zykton-B gas crystals. [11] A large pit can be seen behind both Gas Chambers and Crematoria I and II; it is probable that these were the pits used in summer 1944 for the open cremation of bodies which could not be handled in the crematoria. Measurement of Gas Chambers I and II by NPIC photogrammetrists provided construction data on the crematoria not available from the architectural plans.

Numerous sources speak of the well-kept lands and landscaping around the crematoria; some described the buildings as “lodge-like,” “industrial looking,” or having a “bakery-like” appearance. These descriptions are borne out by the imagery of 25 August 1944 in which a park-like rectangle is visible. In the imagery of 13 September 1944 landscaping is visible around all four extermination facilities. Although survivors recalled that smoke and flame emanated continually from the crematoria chimneys and was visible for miles, the photography we examined gave no positive proof of this. [12]

The imagery acquired on 13 September 1944 provides a unique view of Gas Chambers and Crematoria IV and V (Photo 7). Located among the trees of the “Birch Wood,” these facilities could not be seen by surviving prisoners in the camp. They were of a different design than Gas Chambers and Crematoria I and II; they had two rather than one chimney each, and were built totally above ground rather than having underground sections. An additional piece of information, not included in Photo 6, is the view of two large buildings some 500 meters west of the disinfection block. It is probable that these are two of the 1942-43 era extermination facilities used prior to the construction of the four main gas chambers in 1943.

Deactivation and Dismantling of the Complex

Background: When imagery of Birkenau was next acquired, the operational status of the camp had changed radically. By 29 November 1944, the Nazi war effort on all fronts was on the verge of collapse. A dramatic though futile revolt of the Sonderkommando had occurred on 7 October 1944 at Gas Chamber and Crematorium IV. [13] Extermination at Birkenau was officially terminated on 3 November 1944. The first stages of evacuation of the prisoners and the technical equipment began shortly thereafter.

Photo Evidence: Photography of 29 November and 21 December 1944 enables us to monitor the progress of the Nazi evacuation efforts (Photo 8). For the first time since Allied photography had been acquired, no train is located in the Birkenau railhead. The exterior of all extermination facilities, with the exception of Gas Chamber and Crematorium IV destroyed on 7 October 1944, appear to be intact. The dismantling of Section III of Birkenau has begun.

On imagery acquired on 21 December 1944, the progress of the evacuation effort is clearly discernible. The electrified fence around Section III and the guard towers there have been dismantled. The former location of the various barrack blocks and support buildings can be identified. The light snow cover provides an aid to our interpretation efforts by highlighting soil marks and depressions, making it easier to identify man-made disturbances. There is a clear view of Gas Chamber and Crematorium IV’s former location. [14] Additionally, Barracks Block B II/C II has been destroyed, probably by fire. We were able to find no reference to this event in the collateral material.

Photo 9 details Nazi efforts to dismantle the technical equipment at Gas Chambers and Crematoria II and III. We can trace the dismantling of the special security fencing around these installations, the removal of the roofs and the underground dressing rooms. the dismantling of the chimneys, and the filling of the pit to the rear of Gas Chamber and Crematorium III. As far as we know, this is a unique photo of that activity.

Evacuation

Background: The final period of Auschwitz is that immediately prior to the evacuation of January 18-21, 1945. By that time, the Nazis faced defeat on every front and were trying desperately to erase all traces of the extermination program. When prisoners could not be evacuated, their destruction was the alternative. Many of the Auschwitz facilities had, in fact, been dismantled and shipped to Germany for use in other concentration camps.

Photo Evidence: The heavy bomb damage inflicted upon the I. G. Farben complex is visible in Photo 10. This 14 January 1945 imagery revealed more than 940 bomb craters and 44 damaged buildings at that facility.

The camp at Buna (Photo 11), is still operational as evidenced by the melting snow on the barrack block roofs. Cleared footpaths and streets are further evidence of movement in and around the compound.

Auschwitz I is also occupied on 14 January 1945 (Photo 12). It was the last camp to be evacuated. Snow melt on the roofs indicates that the barracks remain occupied, with one important exception. The lack of heat and presence of snow on the roof of Barracks Block 10, site of the infamous medical experiments, indicate that it is empty. [15]

Imagery of Birkenau (Photo 13) also presents an informative and surprising record. Section III of Birkenau has been completely dismantled and evacuated, including the guard towers. The snow cover on the roofs of the Women’s Camp indicates that it had been evacuated. Within Camp II, it is easy to detect which of the barracks are probably still occupied as evidenced by the melting snow on the barrack block roofs. The camp had been partially evacuated. Several buildings had been dismantled in the Women’s Camp since the 21 December 1944 coverage.

The most revealing photographic evidence to emerge from analysis of the 21 December 1944 and 14 January 1945 imagery centers on Gas Chambers and Crematoria II and III. The official Polish investigation stated that these facilities had been dismantled and blown up in November 1944, but this is clearly contradicted by the presence of the installations on imagery of 29 November and 21 December 1944, and that of 14 January 1945. [16] Examination of those facilities shows them to be only partially dismantled. On the 14 January 1945 imagery, however, evidence of final preparations for destruction may be under way. Snow patterns indicate activity by vehicles and personnel at these sites. In any case, they had been destroyed prior to the camp being liberated by the Red Army. [17] Here in a small way, photographic intelligence contributes evidence clarifying the official history of Auschwitz.

Conclusion

Our review of the imagery acquired over the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination complex was interesting and, we think, historically valuable. The photographs illustrate a major historical phenomenon from a new perspective and in some cases provide data unavailable from other sources. Our experience strengthens our belief that aerial photography, interpreted with modern intelligence techniques and equipment, is a research source which could be profitably mined by the professional historian.

Footnotes

| * | Rome East of the Jordan: Archaeological Use of Satellite Photography, Studies XXI/1. p. 13; “Satellite View of a Historic Battlefield,” Studies XXII/1, p. 39. |

| [1] | The “intelligence collateral” for this paper was drawn mainly from O. Kraus and E. Kulka, The Death Factory, New York, 1966; N. Levin, The Holocaust, New York, 1973; and the official Polish government investigations, German Crimes in Poland, 2 Vols., Warsaw, 1946-47, which draw on primary sources. |

| [2] | Kraus and Kulka, The Death Factory, p. 8. |

| [3] | Ibid. |

| [4] | Kraus and Kulka, The Death Factory, p. 132; German Crimes in Poland, Vol. I pp. 88-89. |

| [5] | Kraus and Kulka, The Death Factory, p. 17. |

| [6] | German Crimes in Poland, Vol. I, pp. 88-89. |

| [7] | Kraus and Kulka, The Death Factory, pp. 130-141. |

| [8] | Collateral information indicates that this transport is very likely from the Lodz ghetto. This was the last Jewish ghetto in Poland to be liquidated. This action took place between 2-30 August 1944. A less likely possibility is that the victims were members of the French underground, who are known to have been sent to Birkenau during this period. |

| [9] | It was not possible to specify the nationalities of the groups in the photographs from the collateral information. They might have come from either the remnants of the Lodz ghetto or from Czechoslovakia. |

| [10] | Kraus and Kulka, The Death Factory, pp. 134-140. |

| [11] | Ibid. |

| [12] | The imagery examined from records of the extermination period include 4 April, 26 June, 26 July, 25 August, and 13 September 1944. |

| [13] | The Sonderkommando was a special unit of prisoners forced by the Nazis to assist in the extermination activities, especially in the disposal of bodies. Themselves marked for extermination, one group attempted to rebel. Although they succeeded in destroying Gas Chamber and Crematorium IV, they were all killed. |

| [14] | See The Death Factory, pp. 261-263 and German Crimes in Poland, Vol. I, pp. 90-92. |

| [15] | The SS conducted hundreds of “medical experiments” on prisoners during the existence of Auschwitz. These included pseudo-scientific investigations into infections, attempts to “create” twins, starvation experiments, etc. carried out by SS doctors. |

| [16] | German Crimes in Poland, Vol. I, p. 91. |

| [17] | Ibid. |

Posted: May 08, 2007

Last Updated: Aug 03, 2011